24th February 2021

The following article is intended to be a whitepaper opinion piece and has not been subject to formal peer review process. It is intended to promote dialogue and feedback to develop the article further is welcomed.

NOTE- This article is now outdated and is in the process of being revised.

There is no doubt that over the last few years, sustainability has become a dialogue central to shipping. Starting with an acknowledgement of the need to reduce emissions from global shipping and spearheaded by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), the discussion has voluntarily evolved to become more holistic, encompassing a variety of environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors aligned with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Cooperation at the industry, intergovernmental and NGO level has resulted in some remarkable work towards developing a common understanding as to what will make maritime activities including shipping sustainable in the long term. A notable output relevant to marine insurance and the management of shipping related casualties and oil spills are the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) Principles for Sustainable Insurance[1]. This milestone publication involved a number of leading marine insurers and provides a clear indication of the growing focus of the shipping world to formally incorporate sustainability considerations and metrics in day-to-day activities.

Attention has yet to turn to systematically managing ESG risks and impacts when responding to shipping incidents that potentially result in oil spills or complicated and long-term wreck removal operations. A recent UNEP FI report found that in fact a majority of maritime focussed businesses have yet to implement Blue Economy[2] standards into their day to day business activities[3]. In the world of shipping and marine insurance, casualty and incident management could arguably be considered a core activity. Unplanned, emergency situations involving vessels mean that by necessity, standard approaches and protocols must be less stringent and retain flexibility when compared to planned marine development or interventions (e.g. port developments, dredging operations, other aspects of marine spatial planning). However, the potential exists in this sector to approach ESG risk and impact management in a more standardised way that is in line with the wider progress of industry towards enhanced sustainability.

Several actions such as the UNEP FI publication, the establishment of an ESG working group at the International Union of Marine Insurance (IUMI) and the beginning of sustainability reporting by many marine insurers demonstrates the maritime and shipping communities’ commitment to embracing the challenges of adopting more sustainable practices. The question considered here, against this background is: should the shipping industry implement a general framework for addressing ESG concerns in emergency response and tendered projects (i.e. casualty management, wreck removals and long term oil spill clean-ups)? If so, how could such a framework work to ensure positive results without needlessly adding administrative burden and red-tape? These questions are explored in the following sections.

Maritime incidents garner high levels of media interest, public attention and scrutiny. In these times where social media dictate the news agenda and news cycles are virtually instantaneous, there is a broad scope for inaccurate reporting, negative press and a general sense that “disaster” could have been averted but was not. The degree of work, cooperation, technical expertise and money spent on mitigating and dealing with these incidents is frequently overlooked or insufficiently disseminated to the public. This disconnect was brought sharply into focus by the media’s largely one-sided and negative response to the WAKASHIO incident in Mauritius in 2020. It would seem that all stakeholders in the maritime emergency response sector would stand to benefit from the development and adoption of ESG focussed frameworks to guide response.

Implementing a more formalised and coordinated approach to the consideration of ESG factors during emergency response could have the benefit of not only ensuring the best decisions are taken during an emergency, but also provide peace of mind to the public affected and the media reporting an incident.

It is unlikely that a rigid, prescriptive framework would be productive: adding red tape and administrative burden when timely and decisive action is the key to a successful response. However, a general and pre-agreed foundation of guiding principles and best practice approaches could protect against reactive and confused reporting, mitigate the ESG impacts of operations, whilst also providing comfort and security to the general public in the decision-making process. This could ultimately result in a more efficient and technically succinct response to potentially damaging casualties and maritime incidents.

In general, the management of maritime incidents can be divided up into two broad categories, which will also influence the type of appropriate ESG management framework that could apply:

Whilst the process for identifying relevant ESG factors and the finalised material assessment would probably be similar for the two scenarios, the final outputs and potential tools for implementation and means of verification might be different.

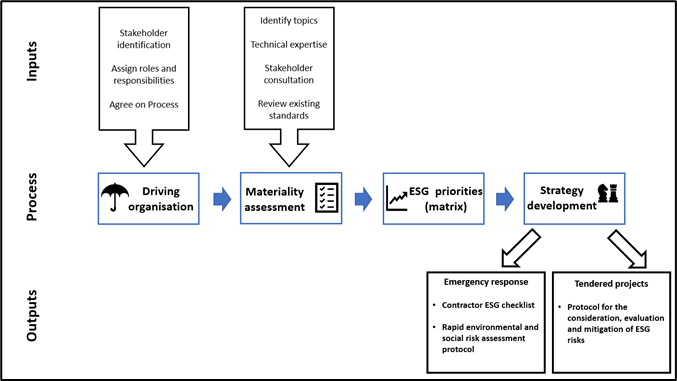

Figure 1 provides an overview of how the process to develop ESG standards for emergency response and tendered projects might work. These are described in detail in the following section.

Figure 1 A conceptual framework for developing ESG standards for the oil spill response and salvage industries.

The development of an agreed ESG standards framework would evolve very much along the lines of standard organisational sustainability reporting. There are well -used approaches and international Standards organisations (e.g. GRI and IFC). Critically, however, lessons learned from historical casualties and oil spills will also be important experiences to guide the ESG material topic assessment phase and the nature of outputs/implementation.

Driving organisation: The crucial first component would be to identify whether there is a need and a desire for ESG considerations to be incorporated into standard operating procedures in emergency response or tendered projects. This would require an initial round of consultation with relevant stakeholders and a singular body to take ownership and control of the process if the outcome of initial consultation deemed it necessary.

Material topic assessment and consultation: This is the process of identifying, refining, and assessing the numerous potential environmental, social, and governance issues that could be relevant and affect an emergency response or a tendered project. Economic and technical factors influencing success and importance to stakeholders may also be considered here so that the relative importance of all factors may be measured.

Once identified, material issues are prioritised and condensed into a short-list of topics that will inform the rest of the process. The process is well-defined in the field of organisational sustainability reporting but could be adapted in this context to identify the most important ESG issues that stakeholders consider to be important in both emergency response and tendered projects. In summary, the material topic assessment has six phases:

Finalised ESG material assessment and strategy development:

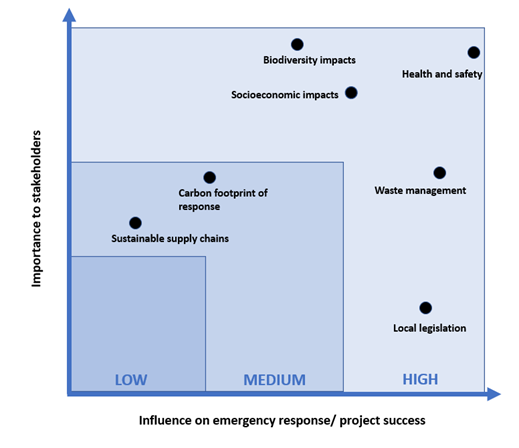

Upon completion of surveys, results analyses will identify the most important material topics both overall and by stakeholder group. These results can be mapped in a chart to provide a visual representation of the relevant priority or significance of material topics (see Figure 2). The X axis would have been defined by considerations that influence the success of a response, as reviewed by technical experts with response experience. The Y axis would be dependent on stakeholder responses in terms of what they deem to be the most important to them. Stakeholder consultation may find that ESG priorities will differ between emergency situations and long term projects. If this is the case, the process can be divided between the two scenarios at the start of the assessment.

At this point, depending on guidance of those involved and if it has not already done so, the process would likely branch into two clear steps: active emergency response and long term projects.

Figure 2 Example material assessment matrix. The figure is for illustrative purposes only and is not based on a real assessment. A real assessment would likely include many more topics.

A summary of potential outputs/ implementation strategies is shown in Table 1. and described in greater detail below.

Emergency response

A document including a checklist to include minimum ESG requirements for contractors to attain. These requirements would be based on the findings of the material topics assessment and would likely include comprehensive Health, Safety and HR policies. As well as outlined approaches for fairly and equitably engaging local staff in responses outside their headquarters’ country and complying with local labour requirements.

The means of verification could include the submission of relevant documentation by the contractor to be “accredited” according to this code of conduct. Review by independent auditor or “accrediting” body.

Auditing during an emergency response by independent advisers on site to provide technical advice.

Response to casualties or oil spills will frequently require rapid decision-making to prevent greater or more significant damage. After the fact, these decisions are often subject to speculation, what-ifs and general questioning as to whether an alternative would have been better. A core tenet of emergency response is that you can only make decisions on the basis of knowledge you have at the time. Unfortunately, due to the time-pressures, these decisions (and the consideration of the options that precedes them) are rarely documented in a way that adequately stands up to external questioning. Especially by stakeholders who may not be experts in the subject matter.

A rapid- environmental and social risk assessment protocol could be developed to document the evaluation of alternatives and decision-making, whilst considering the most important and relative ESG factors identified by the materiality assessment.

A good example of where such a protocol would have been useful is in the case of WAKASHIO. The bow section was towed for sinking into deep water on 24th August 2020. The bow section had broken and was loose. Incoming poor weather meant that the only alternative would have been to attempt to secure the forward section along the coral reef. In all likelihood, such an arrangement would not have withstood the monsoonal weather, leaving the section to be pushed along the reef causing further physical damage. The bow section contained no significant pollutants, was cleaned as much as possible from debris and any remaining oil was restricted to the stern section. From both a safety and environmental risk perspective, the decision to sink the forward section in deep water was the best option. However, the fact that it was the best alternative out of a selection of undesirable options might have been more acceptable if demonstrated against the possible risks of other alternatives, given local environmental and economic sensitivities (i.e. the presence of a coral reef).

Tendered long term projects

For projects that undergo a tendering process (such as the advanced stage of an oil spill response or a complex wreck removal), an ESG framework to guide the tendering phase would not only provide a degree of control over the practices of the winning contractor, but also provide an opportunity to demonstrate the maximum possible environmental and social stewardship. Formalised environmental and social risk assessments are part and parcel of any marine spatial planning project. There are numerous standards and best practice approaches in use all over the world, in many places legally mandated. However, in planned development projects, these studies may take years. To remain practicable and not delay progress, the following approaches to risk assessment could be incorporated into the tender and eventual project management process:

Considering ESG factors at all stages of a wreck removal project would also dovetail succinctly with the growing focus on waste management in response to maritime incidents as well as the work of IUMI’s ESG working group with its focus on sustainable ship recycling

There is considerable scope and merit under current conditions to consider more formally integrating ESG considerations into response of shipping related incidents such as oil spills and wreck removals. The overall objective would be to develop a system that can be flexible enough to apply all over the world, not slow down emergency response processes and decision-making but also aim to make a real difference in how environmental and social risks to these incidents are managed. This article has proposed a general approach, loosely based on standard practice approaches but advocates the integration of the response community’s experience from previous cases. The key points of developing an ESG management framework would be:

[1] https://www.unepfi.org/psi/the-principles/

[2] World Bank definition: the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, improved livelihoods, and jobs while preserving the health of ocean ecosystem.

[3] https://www.unepfi.org/news/themes/ecosystems/rising-tide-report/

[4] https://www.ipieca.org/our-work/sustainability-reporting/sustainability-reporting-guidance/